Neeta Patel wrote this around the end of her senior year for a day in the near future:

you are about to begin listening to the annual class day speech. relax. concentrate. you are graduating from princeton university tomorrow, eleven am. dispel every other thought. let the world around you fade. best to close your eyes. for once this long weekend, allow yourself to see absolutely nothing but the after image of the back of that kid’s head in front of you. just listen now. are your eyes closed yet?

The text marks more than a passing resemblance to one written by Italo Calvino. Published in English with a stunningly self-aware cover in 1982, If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller is a book of beginnings.

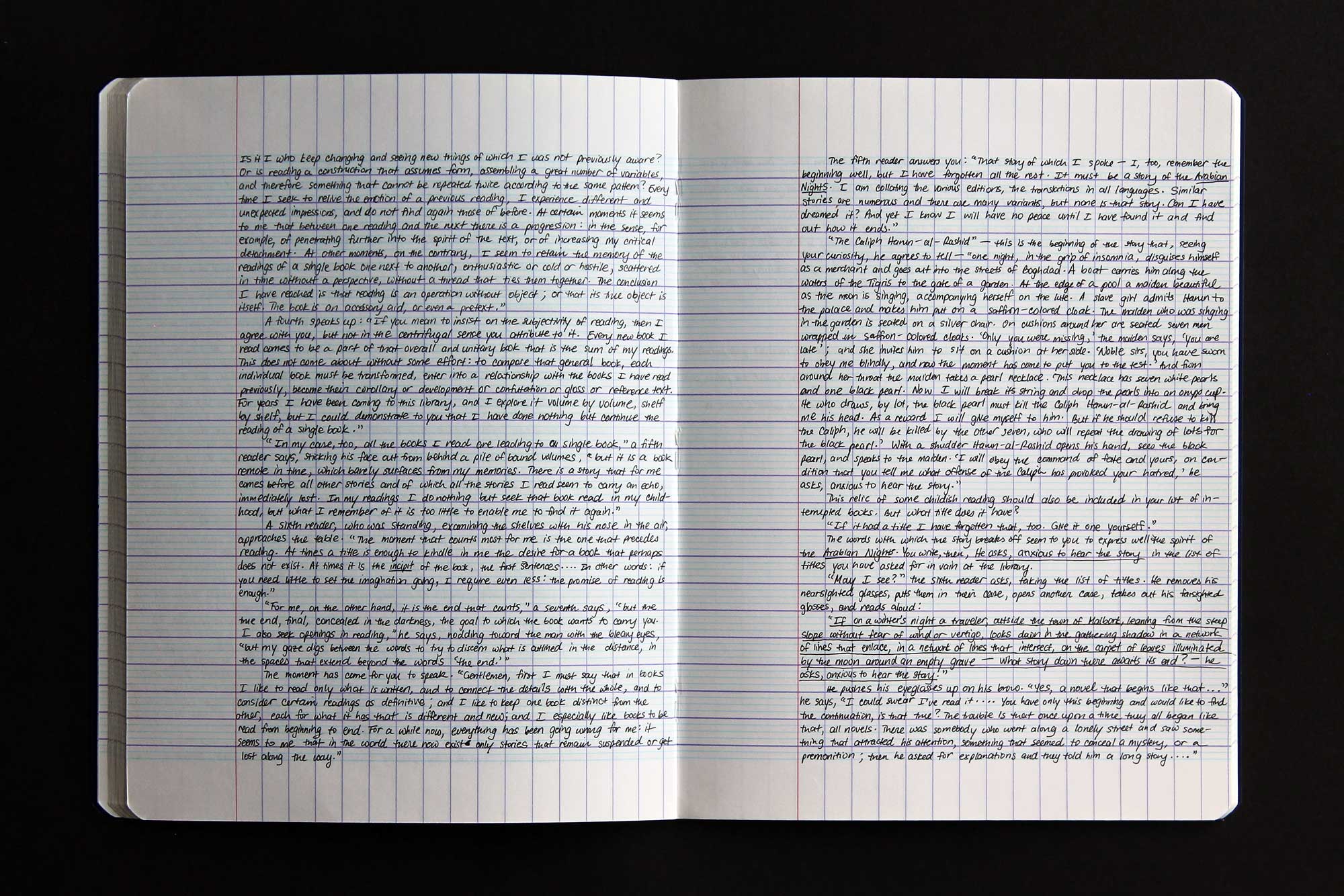

Wikipedia calls it a “frame story”—frankly a new term for me where the narrative is about the reader trying to read the story. It’s no surprise that Neeta's text finds that form as she had spent the previous summer trsanscribing Calvino's novel into a series of notebooks in her own, rather specific, handwriting. Her pages were eventually scanned and reprinted in a series of facsimile editions. A page of her book looked like this:

Anyway, back to her speech, which continues:

find the most comfortable position: seated with your feet firmly on the ground, or maybe you prefer them crossed. left over right or right over left? arms folded across your chest. or maybe you’d rather your hands folded in your lap. put them on your head if you like. careful, don’t hit your neighbors with your elbows. apologize if you do. there. maybe scoot down in your chair, lean back a slight bit. is that better? alright, you know best. of course, the ideal position for the next five minutes is somethingyou may never find. take off your shoes, if that helps.

it’s not that you expect anything in particular from this particular speech. you’re the sort of person who, on principle, no longer expects anything of anything. there are plenty, younger than you or less young, who live in the expectation of extraordinary experiences: from books, from people, from journeys, from events, from college.

She (finally) reveals a bit more context:

you cast a perplexed look to the person sitting next to you (or, rather: it was she who looked at you, with the amused expression of someone who cannot believe that this is the chosen class day speech she’s being forced to listen to, only to forget the words in a few minutes’ time).

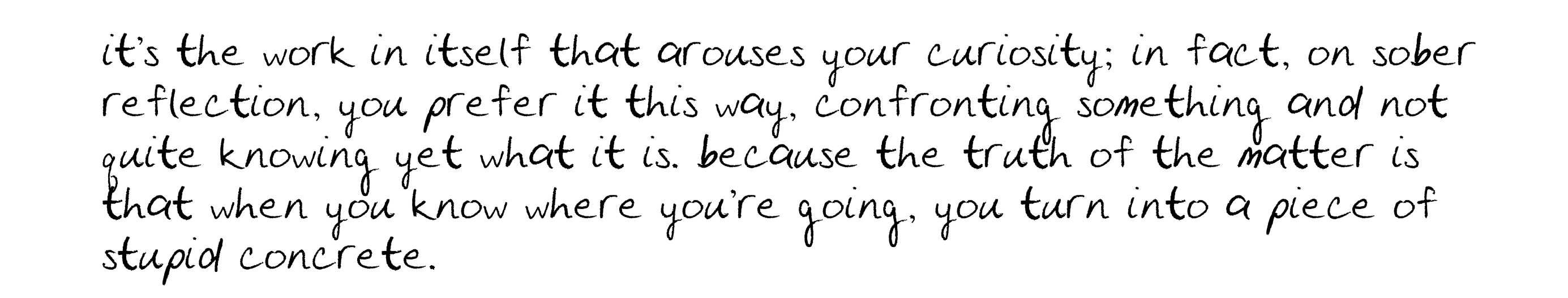

are you disappointed? let’s see. perhaps at first you feel a bit lost, as when a person appears who, from the name, you identified with a certain face, and you try to make the features you are seeing tally with those you had in mind, and it won’t work. but then you goon and you realize that the speech is readable nevertheless, independently of what you expected of the unexpected speaker, it’s the work in itself that arouses your curiosity; in fact, on sober reflection, you prefer it this way, confronting something and not quite knowing yet what it is. because the truth of the matter is that when you know where you’re going, you turn into a piece of stupid concrete.

Reading here, you are getting only a slim portion of the actual effect. The text was typeset in Neeta's handwriting, like so.

A point she unpacks next.

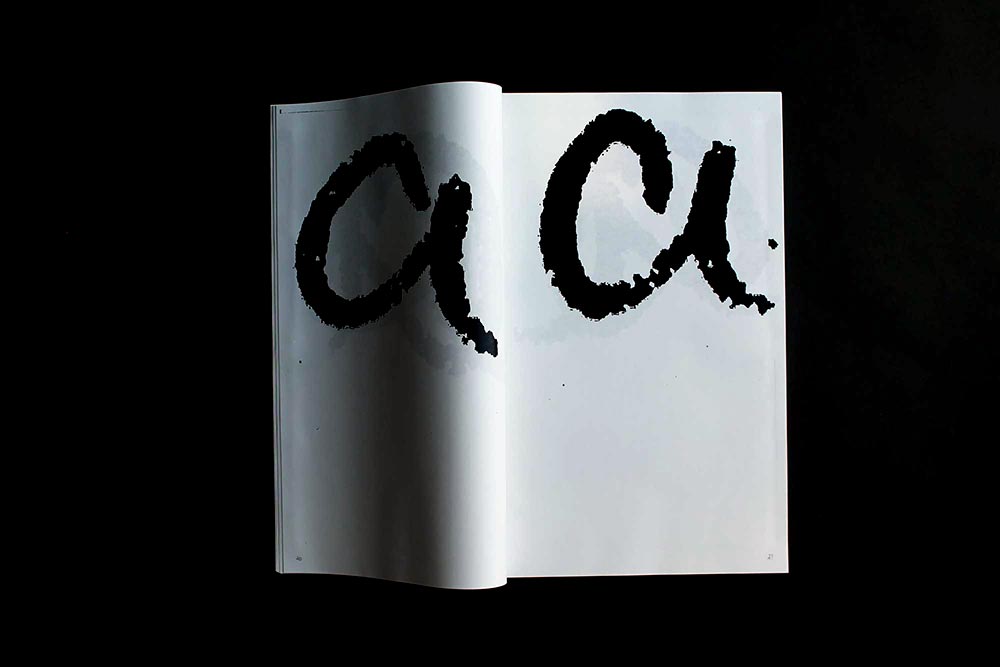

allow me to recount to you a brief story of an alphabet that might help make this right now a little more concrete. this speech is brought to you by a font i designed during my time as a visual arts major here. it’s a font based on my handwriting. maybe you’ve seen it around campus, via posters i designed or in the halls of one eighty five nassau street. designing this font took the better part of two years. it’s actually kind of absurd because this typeface, if you could see it, does not look so sophisticated (it’s actually pretty wonky and awkward), and it’s a wonder that it took anything more than a few hours to create, let alone two years.

November 20, 2023

Neeta Patel’s Handwriting

Neeta Patel’s Handwriting

Readings

Class-Day-Speech.pdf (Neeta Patel)

A-Reexamination-of-Some-Aspects.pdf (Sheila Levrant de Bretteville)

Resources

Visitors

David Keshavjee

Jon Gacnik

Neeta Patel